This was the adventure that taught me that a bucket list vision can become reality. This same adventure was so rich in experience that it sparked a deeper interest in journaling, ultimately leading to this blog. This is a story of friendship and possibility.

Text from Allex, November 30th 2022:

“I’m taking my split board to Germany with me in February so I can do the Haute Route and I need a bro to go with.”

My reply:

“Sounds great!”

“What’s the Haute?”

I agreed to the proposition immediately because I knew that best way to have an adventure is by simply being down to have an adventure, I didn’t need to know what the hell the adventure actually was.. Having already agreed to join, I googled the subject. The Haute Route is a famous passage through the Swiss and Austrian alps between high-altitude mountain huts.

“Damn looks incredible” I added to the text string.

Glaciers and avalanche terrain would be crossed in an unfamiliar mountain range on the other side of the world. Even without asking, it was understood that we would embark on this endeavor without a guiding company which wasn’t really a choice to save money–and it’s not that I had enough mountaineering experience to obviate a guide–it’s just that Allex and I liked running our own show. It’s riskier and more rewarding.

In the following weeks, we discovered that vacancies in the mountain huts we needed to stay in were gone. Not surprising that a two month lead time for a world famous circuit that thousands of people have on their bucket lists was not planning far ahead enough ahead. So Allex and I pivoted to another noteworthy tour: the Silvretta Traverse. Before we had any other bright ideas like checking this route for vacancies, I bought a plane ticket so that we could lock things in.

A week or two before departure, we finally started to get our things in order. We scrambled to book spots in the huts (Allex’s girlfriend at the time, and now wife, Tanya–a fluent German speaker from Bulgaria–mercifully pitched in and totally saved our asses communicating with the hut management). To make the trip work out with hut vacancies, we’d have to reverse the standard direction of travel. At the same time as making hospitality arrangements, we learned glacier rescue rope systems and rounded up the necessary gear like ice screws, snow pickets, headlamps, crampons, wool long johns, two pairs of underpants…not nearly enough socks.

Departure day came suddenly and I was off to meet Allex in Munich. The plane flight kicked off a 36 hour stint on the move without sleep, fueled only by stoke.

At Chicago O’hare Airport, I exited security to workout in the central hotel gym thinking I would pass out on the international flight and wake up refreshed in Germany. Instead, I didn’t sleep a wink. When I touched down in Munich, I finally met up with Allex and met Tanya for the first time. I probably made a poor first impression because I was delirious from travel and sleep deprivation.

Getting to Europe was only the first leg of the journey that day, which was followed by a blur of memories: failed attempts to pull cash from an ATM, shawarma, saying goodbye to Tanya, a narrowly made bus connection into Austria and surreptitious bribe demands from a bus hand (unofficial tourist taxation), the Alps rising into view from a bus-seat window, Turkish men threatening to fight each other near an Insbruk brothel, a quick stop for a cold beer, getting evicted from first class-class train seats, walking seemingly for miles with 40 lbs of gear on my shoulder and then realizing we had gone the wrong way and having to turn around. Finally, the relief of a bed made for a tiny person that was somehow the comfiest thing I remember ever experiencing.

Landeck was a fine town to wake up in. The miniature size of the hotel room was made up for by a hearty breakfast. Our packing had left a bit to be desired and we stocked up on final supplies before catching the bus to Wirl where our trek into deep mountains would begin. The bus navigated a steep and windy road between mountain villages where bright eyed youngsters dressed in ski regalia got on and off. The children were cheerfully familiar with bus driver who seemed affectionate and protective, telling us a the story that a close-knit mountain community exists in the area. We were dropped off where the road made its way up a long valley lined with sheer mountain hillsides. During the winter, cars can go no further as the road isn’t plowed and its snowy covering is groomed into a ski and snowmobile track.

At this point it’s worth mentioning that I had left a deep snow year in Montana for the worst year anyone can remember in the Alps–isn’t that just how things work? Anyhow, the long period without snow eased fears of venturing onto thin snow bridges concealing deep crevasses in the glaciers that lay ahead.

We pushed off and skinned for miles up the valley. Moleskin came out to ease hot spots developing in our boots and to prevent blisters from forming. The unseasonably warm weather had triggered wet slides all along the valley sides; the landscape was in flux, February felt like May. The warmth put us on edge, but we had yet to discover that we would climb much higher in the mountains into cooler terrain before the day was over. Over the miles, we leapfrogged with a couple from Basque country that were on a similar trek and we exchanged light hearted banter in a smattering of languages. Stopping for a short rest, Allex spotted an Ibex high on a mountain face. We watched for a while, enraptured by this exotic creature.

As the evening approached, we reached Silvretta-Stausee–a lake that sits next to the highpoint of the road we had traveled on. There, we found Silvretta-hause hotel, which was accessible in the winter by cars coming from the other direction and it was therefore well stocked with food and tourists. We were still a long ways from our destination, but Allex and I were already pretty tired and the thought of warm food and a delicious Austrian beer easily lured us up onto the patio.

Austrians are a zesty folk and the waiter was no different, bluntly refusing our attempts to order in English. I awkwardly stumbled through speaking in German, “Ich möchte ein dunkel, Danke schön.” I exclaimed, desperate for a cold beer. His expression softened almost imperceptibly but winkles of amusement appeared at the corners of his eyes. The beer ordering went well, but his impatient demeanor made us hurry through ordering food. I asked for Haus Wúrst, imagining that I couldn’t go wrong with the house standard of a famous germanic food. Allex ordered “SpongeBob.” Immediately I felt that I had blown it. Allex had been in Germany for weeks now, and his girlfriend was basically a native. I suspected that he had secret local’s knowledge of this amazing SpongeBob dish and it was a delicacy that would make me jealous. But when our food arrived it became clear that he had ordered from the kid’s menu: two ungarnished hot dogs sat atop a handfull of french fries. I felt bad enough to share some of my delicious Haus Würst.

We floated the idea of staying at the night here, but I was determined to reach our first hut reservation. I can’t recall if I had one beer or two, but I was definitely tipsy as we launched back onto the skin trail. We skittered around the lake laughing about SpongeBob and sometimes falling over, at risk of sliding down an icy slope onto the broken ice that covered the water. We were all jokes and took a lot of shitty pictures. But sunset fell quickly and the toils of skinning induced sobriety.

We referenced Fat Map repeatedly to get an idea of what lay ahead of us and when we would reach the first hut. Without service it was hard to get our position dialed. Onward we trekked, guided by REI headlamps and fueled by occasional gummy bear breaks. We passed a sign declaring, “Weisbadner Hütte: 3.” I was thrilled! Only 3 more kilometers? But an hour an a half later there was no hut in sight and the arithmetic just wasn’t adding up. Surely we traveled at least 3 kilometers per hour: surely we should be there. That’s when Allex realized that the signs were written in hours of travel and not distance!

The final approach to the hut was up a long, steep slope. Darkness and a disorienting nighttime mountain landscape altered depth perception. Time passed slowly as the lights far above us slowly materialized into a building. We found the ski room and then ventured inside, searching for and finding the grumpy Austrian host. I was nervous to interact due to exhaustion and language barriers but there was nothing for it. Despite the host’s poor manners; he seated us next to many fellow adventurers who were enthusiastically downing goblets of wine, and he did is job admirably: despite our late arrival, he brought us a multiple course meal consisting of steaming hot soup and large portions of schweineschnitzeland that we downed hungrily. I have few other memories of the day, except that several euros bought me about 20 seconds of hot water for a shower. Once we reached our bunk beds, sleep came quickly.

The following dawn yielded a clear vista of the marvelous terrain we had entered under the cover of darkness. Across the valley, a turquoise glacier hung on the side of Piz Buin, one of the many rock-crested peaks that enshrined the horizon. Piz Buin looms at 3312 m, one of the highest summits in the area and todays destination for many fellow trekkers. In fact, we could see skiers making their way up the approach. Having started early in the morning, they were far away and nearly imperceptible against the bulk of the mountain. Allex and I wanted to recover from the previous day and chose an easier side trip in the opposite direction.

We filled up on the breakfast fare that I learned is standard throughout the huts: muesli, yogurt, toast, jams and butter, thin sliced cheeses and cold cuts. Although breakfast was laid out for us, we had to ask for multiple small carafes of coffee before we had our fill. It’s unlikely to be a best practice, but several trekkers took additional provisions from the breakfast table for their lunch. Allex and I were already stocked up with summer sausages, cheese, candy, and other energy-dense foods.

Immediately following our departure from the hut, we cut our way up a steep south-facing slope. Freeze-thaw cycles had turned it to icy hard pack. Allex installed binding crampons to keep himself from sliding backwards or down the slope in an uncontrolled tumble onto rock fields. I relied on upper body strength to stab my ski poles into the crust and I used my poles to wrestle my way up the hillside. Ski crampons and a whippet seem prudent in retrospect, but with this being my first major ski tour, I lacked the experience to know this in advance. At one point I slid back more than I advanced. There was so little hope of skinning up further that I pulled my skis off and boot packed the rest of the way up the pitch.

The initial climb brought us to a rolling, low angle path up a cirque enclosed by rocky chutes. We marauded forth for several miles until we gained the final approach to mount Rauher Kopf and the angle surged dramatically. We battled our way up more icy switchbacks to a saddle where I left my skis and Allex left his split-board so that we could climb our way up the rocky summit by foot. My hard plastic ski boots were slippery on the rock surfaces and the protruding toe piece made it difficult to climb in the way I was used to. These unexpected conditions caused me to tense my body and I gripped handholds forcefully as I climbed. At the top of the mountain we found a steel cross, a foreign object to find high in the mountains; another reminder that we were far from home. For the first time, we had a 360 degree view of our surroundings. Exhilaration punctured through our labored breathing.

The Alps are unlike any mountains I’d visited. The gravity of their steep chutes, glaciers, and naked rock faces is paired to unrivaled accessibility. Adventurers from Europe (but really from all over the world) flock to these peaks and we were never far from other adventurers. As we traversed mountainsides, large guided tours could be seen like trains of ants moving between destinations. Often, small groups and single adventurers crossed our path. Conversation revealed that their travel plans varied widely from the main trekking corridors, and at times, questionably so. The proximity of these serious mountains to major population centers combined with the availability of well-stocked huts in nearly every major valley creates a culture of accessible alpinism in Europe that’s vastly different from my experience in the US. In this choose-your-own adventure environment it was easy to forget how serious the terrain can get, which is very serious.

Heading back, hours of ascent was recovered in minutes once we strapped on skis/board and took turns carving down the mountainsides. Despite the generally poor conditions, shaded aspects held soft snow and we blissfully found weightless turns on a steep slope. On the sunbaked aspects, we fell back on years of skiing experience safely navigate back down. Hardpacked ravines felt like halfpipes. Smooth terrain would suddenly be interrupted by icy washboards.

Concluding our day’s journey, the sun was low on the horizon, but its last rays warmed the hut patio, where ourselves and many other trekkers scattered gear and dipped inside the hut, returning with frothy beersteins–cheersing each other in celebration of a successful and safe day of mountain fun. Drinking beer, Allex and I reminisced on the day’s adventure, recalled college memories, and shared philosophies and plans for the future.

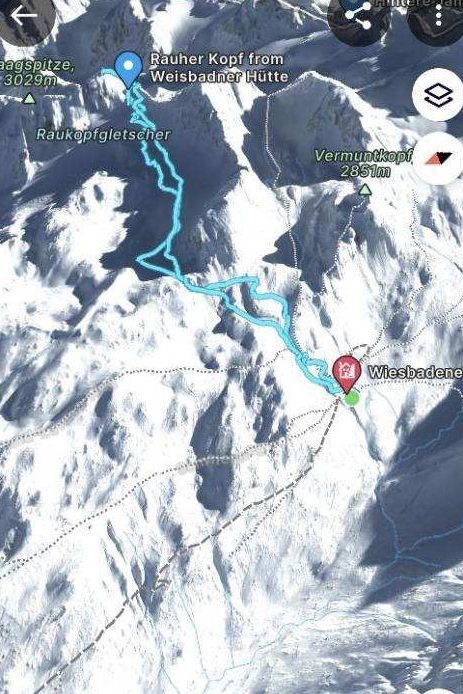

The route for the side trip up Rauher Kopf that we completed on day two of our tour.

From our vantage point on Rauher Kopf, Allex and I had seen into the nearby valley where we were headed next. The jagged peaks, endless chutes, and magnitude of the mountains pulled us onwards to explore the new area. On the morning of day 3, I was relieved leaving Weisbadner Hütte. I wasn’t just excited for the next stage of the trip but I was also getting tired of the spot. Settling up with the hosts the night before, I had been surprised by the balance: the pricing structure for room and board was surprising but we were assured that the bill was correct. For a moment I was worried that we would run out of cash, but we had enough.

Leaving Weisbadner, we voyaged to the south and to the east up a long pass. The sustained climb led me to experiment with different types of ski movements and their efficiency. As we fired up the slope, in spots I kicked out off my skins like a half-assed nordic skier. The glide improved my pace. In other areas, it was best to break through a crust and stomp down on the snow underneath to create a steady platform before pushing off. From behind, a lone skier rapidly gained on us. He greeted us warmly and then continued on his way in a totally different direction. He had come from our original starting spot just that morning and would go a much further before night. This middle-aged Austrian athlete was taking full advantage of his backyard, ranging far between mountain huts. For the first time, I saw the type of athlete and attitude that drove the skimo sport movement and gear evolution, which is less concerned with reaching highly technical descents and focusses instead on moving fast through backcountry and covering great distances. I imagined that this fast and light approach is a natural progression considering the extensive hut infrastructure in place throughout the Alps allows for swift travel without the burden of excessive gear.

Near the top of the pass, Allex spotted a steep, north-facing couiar that we wanted to skin up and earn elusive untracked turns. Caution impelled us to dig a snow pit and gauge stability. Over the next hour we shoveled through the heavy snowpack, revealing and taking notes on the crystalline strata that were revealed. Our journey through this recording of the prior winter conditions showed several weak layers and the deal was sealed at the very bottom where we discovered a depth hoar base. The slab seemed unlikely to go, but if it did, it might bury us deep in an icy grave in front of a small terrain trap at the bottom of the slope. We decided to walk away, safe but disappointed.

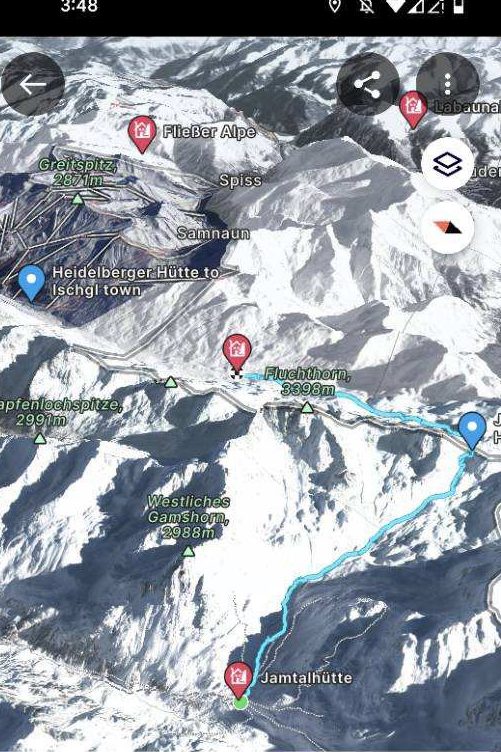

Our frustration died quickly. Reaching the crest of the pass, we were rewarded by one long, sweet descent all the way to Jamtal Hütte. Below us we could see a party traveling up what we would travel down. The route first descended to a glacier and then afterwards angled alongside the stream emanating from underneath its icy mass. The continuous traffic and low angle made us confident about the snowpack. Hopturns down the side of the steep and icy ridge gained us the shaded glacier below, where we found soft snow. We cut it loose. Striking a compromise between following the skin tracks to avoid dark crevasses and searching for untouched powder, we rocketed down the pass. I launched off a small boulder and let out howls of joy as we sped along, “Yyeeewwwww!”

Jamtal Hütte is the crown jewel of the Silvretta Traverse. Its surroundings are winter Rivendell; an escape from the machinations of western society where the only responsibility is to explore the high snow fields punctuating the naked sawtooth peaks that enclose and shelter a long, steep valley. The high angles and northern aspects protect the snow from sun. Not only is the valley special, but the hut is unparalleled. We were surprised by automatic doors leading to the main dining area. Smiling hosts rented us towels and sold us shower tokens that lasted for minutes of delicious hot water. Outdoors, a flagstone-paved patio made a welcome resting spot for the afternoon beer. In every direction, there were massive vistas of precipitous peaks. Right from the door you could skin up a chute and get hundreds of feet of good turns. The mood here was jovial.

Day 4:

This day stands out in my life. Striking off, I recall a low cloud ceiling and fog occluding our destination. We planned to head up the valley and then up a steep set of mountain faces until we reached mount Hintere Jamspitze on a sharp ridge line marking the border between Austria and Switzerland. The weather was questionable, but the opportunity irresistible. From the top of our destination, we’d be able to ski down a seemingly endless snow field, thousands of feet to descend at once.

We transected streams, ridges, and rolling hills; navigating around frosted boulder fields. We’d enter side valleys that we hadn’t even realized existed because from a distance they seemed insignificant compared to the larger cirque. The unexpected topography confused our trail but we were reassured by occasional encounters with skin tracks. We were tired from days of physical effort, and when we reached the bottom of a glacier that encompassed the probable next leg, blowing snow and wind chilled us as we stopped to rest, refuel, and contemplate. Conversation was minimal as we considered our strategy for advancing in the near white out conditions that now swept over us.

When we had departed that morning, a large guided tour was ahead of us by about 20 minutes and seemed to be going in a similar direction. Our paths split early, but we often spotted them traveling parallel to us far in the distance. Pride drove Allex and I ahead. The last thing we wanted was to be bested by an entire cumbersome group. This provided spring to our step. We did not stop long on our rest and we headed up the glacier boldly. In the flat light and blowing snow, uphill was our only sense of direction.

For hours we pushed ahead without point of reference for how far we had come or how far we had left. At some point we departed the glacier, evidenced by unexpected rock bands that we perceived through the fog. We searchingly traversed our way around these bands and continued on our way up, sometimes getting cliffed out and having to turn around. We traveled in this manner with little sense of time until suddenly the face of Hintere Jamspitze broke out of the clouds. Instead of massive, it looked so small. I was disappointed. But my eyes played tricks on me: we were a long ways off and with each stride the naked rock face grew more immense.

The route ascended into a snow-blanketted meadow directly below the peak. The meadow was crowned by shark tooth rock formations splitting the border between Austria and Switzerland. This place had an aura, an electricity to it. We spotted a fractured rock column extending from the cliff face hanging over Switzerland and we knew we had to get on top of it.

I could have spent the day exploring this lofty spot, but the afternoon wore on and the fog was lifting, offering us a promising window for a good descent. I quickly bootpacked up the peak to mark the highpoint and drink in the view, then I came down. We stripped our skins and buckled in.

Hard packed chunder covered the initial pitch, which immediately plummeted into a steep grade with softer snow. We threw caution to the wind and charged down the slope. As I carved down, my eyes picked up a break in the snowpack. My skis crossed a small fissure that hid the icy depths of a crevasse below me. I hoped that my speed would carry me over any weakness in the snow bridge I crossed and help me to avoid whatever large emptiness lay below me. The snow held and then that split second was over.

I had probably crossed over a bergschrund, which is a fissure that forms at the top of a glacier where its fluidic mass pulls away from the rocky headwall that marks its starting point. Better inspection of our terrain might have keyed me into the danger.

Reaching the bottom of our descent, we enjoyed our last night at Jamtal Hütte, ecstatic about our day and about being able to drink beer on the patio. Surprisingly, Adventure groups kept to themselves apart from passing conversation. Perhaps because everyone was already with their best friends and everyone was exhausted.

We’d depart for the last hut in the morning. It felt like our time in the mountains was drawing to a close and I hated to leave this magical place.

That next leg of our trek was a long haul up a meandering mountain valley to reach a windy pass, followed by a bit of a descent, and then endless rolling hills down to Heidelberger Hütte. The trip was catching up to me: the absence of recovery time from work before starting the trip; the outlandish journey by plane, train, and foot to our starting point; and of course, four days of skinning up mountain faces. A diet overwhelmingly of pork, summer sausage, and schnitzel held heavy in my stomach, and I was coming down with a cold. I’m surprised I still digested food. The ascent to the mountain pass revealed that Allex was feeling stronger as the trip progressed. I felt the opposite.

Regardless, it was impossible not to appreciate the beauty surrounding us. Many times we stopped to admire the landscape. Sparkling snow crystals graced the banks of a small creek running down the valley. Breaking free from my headspace, I could replace my superficial pains with appreciation for where I was and what I was doing.

I oscillated between admiration and misery as we summited the pass. Windbare scree patches forced us to remove skis and hike. Cold air tore at us. The environment was unfriendly, but we were surrounded by views of unrivaled majesty. We didn’t linger in this harsh environment. Hoods came up, jackets were zipped tight, and we marched on .

The snow was bad on the other side of the pass. We picked our way down the mountainsides, taking care to avoid barren rock fields interrupting the snow cover. Our low energy made the conditions even more dangerous.

The steeps eventually gave way to flat stretches and occasional uphills. We repeatedly stripped skins and then reapplied them. It wasn’t fun. Allex’s experience was testament to how much better backcountry skis are over splitboards in hilly terrain. Allex disassembled and reasambled his board over and over and over as the miles wore on. At one point he tried skiing downhill with his board broken apart, but splitboards don’t have inside edges and it’s a big leap from snowboarding to telemark skiing without edges. He had limited success.

The Gauntlet ended as we finally crested a hill and found ourselves above the hut. We skied down the last pitch in relative style, hiding the awkwardness of the last four miles. We must have looked pretty good because onlookers on the patio asked if we were professionals.

This last hut, as with all before it, had a totally different vibe. A hot shower and some rest, some snacks, and hot mulled wine revived us. Heidelberger Hütte is known for its cuisine and its tenure: over 130 years old. At the bottom of the valley that enclosed us is the ski town of Ischgl, which is known as the Aspen, Colorado of Austria. Most visitors get towed up the valley to Heidelberger Hütte by snowmobile, and these resort softies looked at us in reverence. Our backcountry endeavors were impressive to them, especially without a guide. Our American flat bill hats made us exotic.

The dinner host was excellent. He shuffled guests to find the most sociable table. He sat us with a group of Dutch (and various other folk) since they’re the best English speakers and some of the friendliest. Cheerful conversation permeated the evening. To celebrate our last night on the tour, we ordered a bottle of Austrian wine that came with a scandalous label. I don’t remember what we ate, but I remember it being delicious. Multiple courses were passed around the table and my appetite was large.

Three inches of fresh snow fell that night. What could have been potentially treacherous but enjoyable in the high country hindered our exit down the valley. We proceeded down the long, flat track for hours–pushing ourselves with ski poles through the fresh powder. I got tired of skinning and skate skied awkwardly on my heavy backcountry gear. Allex didn’t have that luxury on the split board. At one point we pirated a ride on a rope tow that paralleled our path. On the last leg, things finally got steep enough to buckle up and glide into Ischgl in one last victorious descent. We romped around Ischl briefly while we waited for a bus to take us away. We were tired but totally satisfied. What a trip.

Return to Munich was bittersweet, Tanya was super glad to see Allex. I wish I’d had more time to hang out with them. We all had dinner together and I departed in the morning. The overall journey was like a tactical operation: in and out. US-Munich-Austria-Switzerland-Austria-Munich-US. From conception to completion in a matter of months. It was hard leaving behind my homie and this tremendous adventure, but I’m grateful to have had the opportunity. Now I carry these memories that make me excited for a new adventure, and a new adventure is never far off.